In one of the many memorable scenes in Chariots of Fire, the two old Cambridge dons look out the window on the departing Harold Abrahams and lament that his attitude is just not that of an English Christian gentleman.

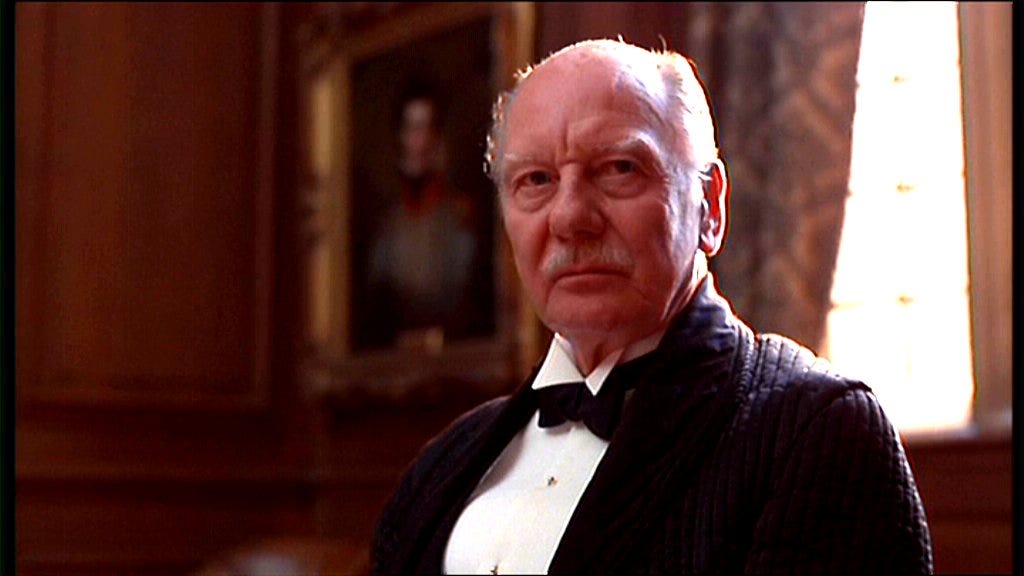

“Well”, says John Gielgud as the Master of Trinity College, “there goes your Semite, Hugh. A different God; a different mountaintop.”

It’s not often that the contrast between the two mountains in Hebrews 12 is alluded to in popular culture. In fact, I think it’s safe to say that this may be the one and only and final time.

Abrahams belongs to the God of Sinai, the Cambridge don is saying—to the smoking, terrifying, mountain of the law. We (he implies by way of contrast) have a different mountaintop, the heavenly Zion, the joyful assembly of the justified.

What’s going on here?

Are the two stuffy academics casting the professionalized pursuit of individual athletic glory (that they see in Abrahams) as a kind of works-based striving for acceptance? Or is it just the hide-bound prejudice of the self-satisfied Christian elite against the upstart pushy Jewish outsider? Or could it perhaps be a bit of both?

This complexity is one of the many layers of meaning that make Chariots of Fire such an entertaining and satisfying story.

At this point in the film, the British establishment (in the form of the dons) is arguing for the spirit of the amateur and against the win-at-all costs professionalism of the modern athlete. Sporting endeavours, they say, are about the creation of character: “They foster courage, honesty and leadership. But most of all, an unassailable spirit of loyalty... comradeship and mutual responsibility.”

Later in the movie, the British establishment (in the form of Lords Cadogan and Birkenhead, and the Prince of Wales) try to dissuade Eric Liddell from precisely these ideals. They try to talk him out of the courageous, loyal, honest expression of his Christian beliefs (about running on Sunday) so as to win Olympic glory for Britain. Which mountain do the British elites belong to now?

The compromised nature of the establishment is highlighted by Liddell’s character. He is also an outsider; a Scottish, non-conforming Christian. In many ways, he represents the calm assurance and joy of the heavenly Zion. He runs with a kind of liberated abandon and pleasure that his rival Abrahams can only dream of, and with a sense of commitment, courage and integrity that the Cambridge dons would surely approve of.

And yet, ironically, the climactic plot device of the movie—Liddell’s Sabbatarian refusal to run on Sundays—suggests that the old mountain of the Law still has some hold on him.

The movie closes (and opens) with another twist—the funeral of Harold Abrahams in the church of St Martin-in-the-fields, Abrahams having converted to Christianity around a decade after the events portrayed in the film.

Recalling all this is making me want to go and watch again for the umpteenth time, and if you haven’t ever done so (i.e. you’re probably under 40), let me highly recommend it.

But before I zip downstairs and fire up my steam-powered Panasonic VCR and rifle through my VHS collection, a word about why I’ve been thinking about Chariots of Fire again after all these years.

It’s because I’ve been reading Hebrews again, and thinking about how important and climactic the two mountains passage in chapter 12 is in the message of the whole book.

As you no doubt know, Hebrews sharply and constantly contrasts the old covenant and the new. For all its glory, the old covenant of Moses is a shadow and forerunner of the ‘things that were to be spoken later’. It testifies and points forward to the new and infinitely better covenant that has now been finally revealed and enacted by the Son. Israel set out on a journey to the promised land of rest, and most didn’t make it. We have set on a pilgrimage to a heavenly sabbath rest, under the leadership and ministry of “a great high priest who has passed through the heavens, Jesus, the Son of God” (4:14).

The contrasts mount up as the book unfolds—the better and final revelation (1:1-4), the better servant-leader (3:1-6), the better sabbath rest, the better high priest and sacrificial atonement made in the better tabernacle (ch 5-10), the better city, the better country, the better resurrection (ch 11), and finally in chapter 12, the better mountain.

In all of these contrasts, the ‘betterness’ of Jesus’ ministry and the new covenant is heavenly. In particular, the sacrificial ministry of Jesus as the one, great and final high priest takes place not in an earthly tent or on an earthly mountain (Jerusalem, Mt Zion). His life is taken on the earthly hill of Calvary, but it is in heaven, in the heavenly tabernacle of God, that he appears and offers himself once for all at the end of the ages to put away sin (9:25-26).

On the basis of that eternal, heavenly redemption, the new covenant people of God arrive at their destination—the heavenly Jerusalem, the heavenly mountain of chapter 12. That’s what all the heroes of faith in chapter 11 were longing for, but never saw, not even those who entered the physical promised land (like David and Samuel and the prophets, in 11:32).

Interestingly, there are two mountains in Hebrews, not three. There’s the earthly Sinai and the heavenly Mt Zion, but the earthly Mt Zion doesn’t feature. As the book unfolds, Israel is redeemed under Moses, receives the law, journeys towards the land of promise, and has a temporary ineffective priestly ministry in the tabernacle to accompany them. But they never arrive. There is no earthly Jerusalem in Hebrews; no temple, only a tabernacle. There are only two mountains (Sinai and the heavenly Zion), because the promise to Israel was never about an earthly mountain but a better, heavenly one.

It is to that heavenly Mt Zion that we have now come through the blood of Christ, through his infinitely greater heavenly sacrifice and redemption. And our response? We must not refuse him who speaks, but fall down before him in submission (12:25-28).

This, of course, is the point of the book of Hebrews, and of the two mountains passage in chapter 12. As much as we love this passage as a key plank in our doctrine of the heavenly ‘church’ (or assembly), its main function is as the high point, so to speak, of the book’s exhortation. Consider what the eternal high priestly work of the Son has done for you; understand where you now stand through the work of Christ; and for heaven’s sake (quite literally) don’t give up now. Don’t drift, don’t droop, don’t shrink back, don’t let your hearts be hardened, don’t refuse him who speaks; but instead, draw near for help to the throne of grace that we now have open access to, lay aside every weight and sin that hinders us, and exhort and encourage one another to stand firm and grow in love.

The Master of Trinity was only half right. It is a different mountaintop, but not a different God.

The same God who spoke in darkness and fire on Sinai is the God who has now fulfilled all his promises through his Son, and brought his people to their heavenly home. Let us continue to serve him, with reverence and awe.