As foreshadowed in last week’s edition, I want to come back to a question that has been niggling away at me over the past few months, and that a number of you have asked about.

The question goes like this:

let us agree that there is only one gospel (not many gospels);

and let us also agree that each person we tell the gospel to will have different questions, and come to the gospel with different cultural presuppositions; any particular conversation or presentation might start at a different ‘entry point’, touch on different presenting issues or questions, and utilise different language or metaphors along the way;

how, then, can each gospel conversation or presentation be the same and yet different? How can the gospel be one thing, and yet many things?

This is a very important question, because it affects not only how we preach the gospel (in evangelistic talks or courses) but how we train everyday Christians to understand the gospel and chat about it with their friends. (I’ve been thinking about this a lot recently, as we revise and rewrite the Two ways to live training material.)

It’s too big a question, in fact, to answer completely and satisfactorily in this little newsletter. But I do have an insight to offer that I hope might move the discussion forward.

Let us imagine that our gospel conversation (or sermon) starts by talking about something good in the world that our friends want more of (like beauty or love or justice) or something bad in the world that our friends want less of (like suffering or injustice or the fact that I’m lonely and my job stinks and I feel desperate).

One increasingly common approach to evangelism suggests that we should frame our presentation of the gospel around these common culturally-framed desires or frustrations in our hearers, by:

affirming what we can affirm that is good about these desires;

challenging the dysfunctional way that we (and our culture) understand them and seek to meet them; showing that our way of pursuing these things doesn’t work;

and then offering the gospel news that there is an answer or fulfilment of these desires, and it is found in what God has done through Jesus.

This is sometimes called the Resonance-Dissonance-Gospel approach.

There’s much to like about it—particularly in how it listens carefully to each person (or culture) and seeks to have a gracious, salty conversation that bounces off the questions and issues of everyday life (in a Colossians 4 kind of way).

But there’s a significant weakness here as well—or at least there often is, depending on how the conversation unfolds.

In Two ways to live terms, the problem happens when we glide too quickly from the second half of Point 2 to the second half of Point 5.

Let me explain what I mean.

For non-2wtl aficionados, Point 2 says:

We all reject God as our ruler by running our own lives our own way.

But by rebelling against God’s way, we damage ourselves, each other and the world.

Coming as it does after Point 1 (God as creator and ruler), Point 2 presents a picture of a good world gone wrong because of our rebellion against the Creator. And so there is plenty of scope to open a conversation of the Resonance-Dissonance variety. God has made a good world—and so beauty and justice and meaning and freedom and a satisfying job are indeed good things that we want and experience. But our ability to experience them is drastically compromised because of our disconnection with the Creator and his ways. So far so good.

But what frequently happens next is that Point 2 is not fully enough explored, and then Points 3-4 are skimmed over too quickly—if I can put it that way—in order to get to the happy ending of Point 5.

Point 5 says:

God raised Jesus to life again as the ruler and judge of the world.

Jesus has conquered death, now brings forgiveness and new life, and will return in glory.

The blessings of forgiveness and new life that Jesus brings are the answer to our frustrated desires and aspirations. In Jesus, the freedom or beauty or justice we’ve been longing for can actually be found. By having a right relationship with God through Jesus, a new life can be ours, both now and forever—the life we were kind of looking for without even knowing it.

However, this too-easy move from Point 2 to Point 5 can be very misleading—because Point 2 not only describes a world gone wrong, and our lives gone wrong, but the fundamental disease of which our negative experience is the symptom. The underlying problem is the wilful fracturing of our relationship with God as Creator and Ruler. Call that ‘rebellion’ or ‘rejection’ or ‘turning away’ or ‘hostility’ or ‘suppressing the truth and embracing the lie’ or ‘sin’, or whatever phraseology is most suitable. But the key move in Point 2 is establishing the larger problem we have with God, of which our current experience is the byproduct—and the larger judgement of God against us, of which our current negative experiences are but a foretaste (Point 3).

Only by getting to Point 3 (as it were) and the reality of ‘death and judgement’ as God’s punishment for our rebellion against him can we coherently talk about why someone dying on our behalf is such good news (Point 4).

And only by establishing God as ruler (in Point 1) whose rule we reject (Point 2), can we coherently explain how the resurrected Jesus has been established as God’s ruler over all.

This can be the problem with the Resonance-Dissonance-Gospel approach. Because the presenting issue (the resonance and dissonance) is often set up in terms of the frustration or dysfunction of our culturally-framed aspirations, then how Jesus’ death is the solution to that frustration becomes difficult to explain—let alone how and why Jesus’ resurrection is so important. Unless we zoom out from our desires and aspirations to the fundamental problem (sinful rejection of God’s rule) and its fundamental consequence (death and judgement), then we will find ourselves struggling to explain the significance of the death and resurrection of Jesus.

And these are the two central, unchanging truths of the gospel: the substitutionary death of Jesus, and his resurrection to be the glorious Lord of all (the ‘Christ’). Or as Paul summarizes it so beautifully, ‘Jesus Christ and him crucified’ (1 Cor 2:2). Our framing of the human ‘problem’ or situation must prepare us to present these twin truths clearly. The way we talk about our current experience (with all its problems and aspirations), must lead us to the point where:

Jesus’ substitutionary death for sins is God’s gracious answer to our predicament; and

the culmination of the message is the resurrected Christ, under whose rule we now gladly and repentantly live.

Our conversations about the gospel will indeed start in a thousand different ways, and our friends will come to those conversations with a thousand different issues, questions, problems, aspirations and attitudes. This does mean that gospel conversations and presentations will differ from each other in all sorts of ways. There is no one form of words that we can take out of our pocket and deposit in the lap of everyone we speak to.

Ironically, Two ways to live has sometimes been seen as just this—a one-size fits all form of words to blurt out onto anyone we speak to. But this was never its intended use. Quite the opposite. It was designed to equip Christians to have a thousand different conversations, starting at different points or with different topics, depending on their hearers—but all of them resolving in one direction, eventually.

The one gospel will always have the same stubborn shape or form. It will always lead to an explanation of Jesus’ substitutionary death for sins and his glorious resurrection as Lord and Ruler of all—along with the response that these two truths call for (faith and repentance).

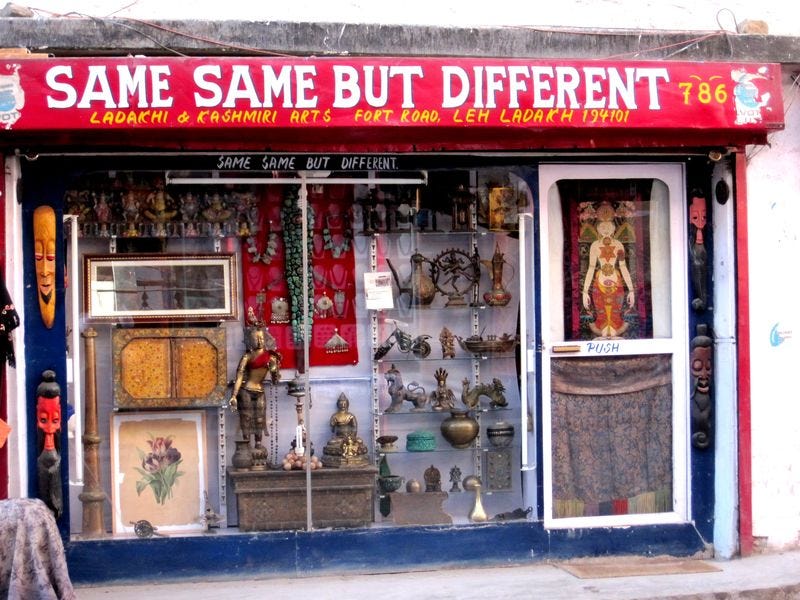

Might this be a way for us to conceive of gospel preaching and gospel conversation as always ‘same same but different’?

PS

Various further questions and caveats come to mind.

For example, must every conversation or presentation or sermon contain the whole thing every time? Must there always be cross AND resurrection in equal quantities? See last week’s edition for thoughts on this.

I’m not sure who first came up with the Resonance-Dissonance-Gospel framework. Tim Keller has recommended it, as has Sam Chan, and Chatraw and Allen in their very comprehensive book Apologetics at the Cross. Like Two ways to live, I’m quite sure that R-D-G can be utilised well or poorly. Done in a certain way, it would not be so different from Two ways to live and other good gospel frameworks—it all depends on how the ‘dissonance’ and ‘gospel’ is done (i.e., whether or not it zooms out to the more fundamental problem of sin and God’s judgement, thus making the gospel explanation of substitutionary death and resurrection coherent). But having seen R-D-G often used in the manner described at the beginning of this post, I thought it was a good foil for discussing the issue.

This whole discussion also raises the interesting question of which aspects of the conversation (or presentation) are actually ‘gospel’, and which bits are ‘preparation or background’ and ‘response’. Regular reader Jack wrote in with a perceptive question on this earlier this week:

Is the call to repentance and faith part of the content of the gospel, or is it a consequence/implication of the gospel?

In favour of the latter (consequence), would be the impetus to restrict the content of the gospel to just the announcement of Christ and his work, independent of any response demanded (though such a demand is clearly still the necessary implication, e.g. in Acts 2:38)—noting summaries like Rom 1:1-4, 1 Cor 15:1-4, 2 Tim 2:8 and their focus purely on Christ.

In favour of the former (content), I've been pondering what kind of news/message/speech-act the gospel is—noting that it is a message that can be disobeyed (2 Thess 1:8, 1 Pet 4:17; cf. Rom 10:16). The ‘obedience of faith’ in Rom 1:5, given its proximity to 1:1-4, I think is also instructive. That a message can be obeyed or disobeyed suggests to me something about what kind of message it is—not just a disinterested announcement, but a summons. A command. And therefore the call to respond is something intrinsic to and constitutive of the message itself, not merely an implication thereof.

Alternatively, is this just somehow a false dichotomy? Splitting hairs? Separating things that ought only be distinguished?

Although it might feel like hair splitting, bringing this distinction into the open is valuable in my view. On the one hand, we don’t want to find ourselves preaching the fruit of the gospel (our response and what it does in our lives) as the gospel itself. But neither do we want to find ourselves preaching a gospel that does not call for and require response—as Jack points out.

Perhaps speech-act theory does help us a little here. The force of the gospel is to announce that certain things have happened, but also to promise that certain things are now true and will happen on that basis (that Jesus is Lord, and now grants forgiveness and new life, and will return to judge). And this same speech-act looks for an expected and appropriate response from its hearer (faith or obedience or repentance, or however we want to describe it).

So yes, Jack—the content and the response are distinguishable, and it’s helpful to be aware of that distinction. But (as you say) they are not separable. I think they are part of the same speech-act.

This is one of the free public Payneful Truths that goes out to everyone on the list every three weeks or so. Hope you enjoyed it (and please feel free to pass it around to your friends). But to get next week’s post, which of course will be an unmissable and life-changing piece of work, you have to rise to the next level …

(Thanks again to all those of you who have become partners, and help keep food on the Payneful table.)