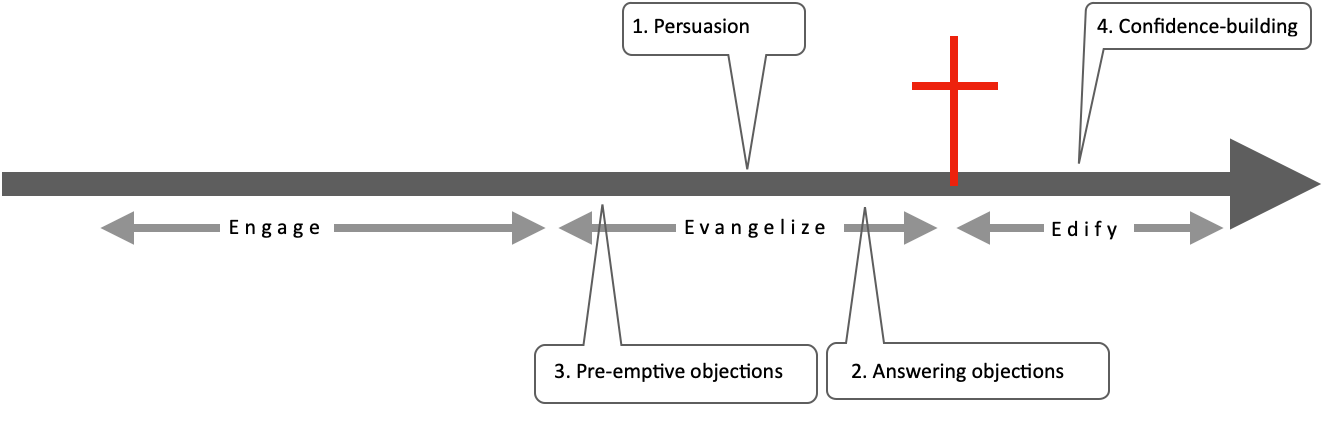

In last week’s edition we began looking at seven types of ‘apologetics’ that are scattered across the spectrum of our interactions with the non-Christian world. Brief recap:

Persuasion: the reason and argument that takes place when we are actually presenting the gospel.

Answering objections: responding to the questions, objections and accusations that arise in response to the gospel.

Pre-emptive objections: clearing away obstacles or objections before we get to actually explaining the gospel.

Building confidence in Christians by fortifying them against the attacks and objections of the world.

Let’s get onto the final three, and some feisty concluding thoughts.

5. God talk

Way down the left end of the process, there’s a kind of engagement and interaction with our non-Christian friends that deserves to be named and recognized.

We might call it ‘pre-evangelistic engagement’ or ‘relationship building’. Ever since I first learned the term in the Two ways to live training course (back in the day), I’ve tended to think of it as ‘God talk’.

‘God talk’ is not really ‘apologetics’ in any meaningful sense, although it may be responsive to a particular question or idea that our friend raises in conversation. It’s simply the personal engagement and conversation that happens as we get to know non-Christian people, and begin to reveal our gospel beliefs in the course of everyday conversation:

when we express a gospel-based opinion about a particular current topic;

when our Monday morning office chat includes what we learned at church the previous day;

when we talk about our own Christian experience in some way;

when we explain our behaviour or choices or opinions in a Christian way;

when we offer to pray for someone.

I think this is the kind of everyday opportunity that Colossians 4:5-6 assumes is taking place as Christians interact with the world, and of which we’re to make good use (by taking the conversation further ‘to the right’, towards the gracious, salty word of the gospel.)

6. Positive reasons

This is another category of interaction which is difficult to label as ‘apologetics’, although it is often described in this way (as ‘positive apologetics’).

It’s the process of offering positive reasons or arguments for Christianity and the gospel, based on the reasonableness or goodness of Christian belief. This kind of interaction commends the gospel as worthy of consideration on the basis of things like these:

the way that Christianity so satisfyingly explains the way the world is, and our experience of it (e.g. both the goodness and evil of man; the existence and nature of love, justice, hope, meaning, personhood, morality, and so on);

the famous ‘proofs’ of God’s existence, which seek to show that good logic demands we believe in the existence of an all-knowing, all-powerful personal God;

studies or examples showing that Christians live deeply satisfying lives;

how the Christian gospel actually answers the deepest questions and aspirations we have as humans;

historical studies that highlight the essential and positive contribution Christianity has made to our civilization.

This is a best-foot-forward kind of approach. Let’s show the world how good and useful and reasonable and attractive Christian belief really can be (and therefore why they should give it a second look).

I’m sure we’ve all employed this kind of argument in conversations or sermons, at least in passing (I certainly have). Some more thorough-going examples of this kind of engagement would be the work of The Centre for Public Christianity, or the argument of John Dickson’s book A Spectator’s Guide to World Religions (let’s think of the religions of the world as fine paintings in a gallery; let me show you why Christianity is the most beautiful).

It’s much harder to find this kind of interaction in the New Testament. There’s the way that godly behaviour ‘adorns’ the gospel in Titus 2:10, and likewise the way that the mutual love of Christian disciples advertises that we are apprentices of Jesus (in Jn 13:34). But these are not attempts to argue for Christianity so much as the natural outcome or byproduct of godly living. Perhaps this is the place of this kind of interaction—to provide incidental confirmation or testimony to the gospel, as the good effects of repentance and faith are seen. In this sense, I’ve heard people speak of Christian community or church life as an ‘apologetic’ for the gospel—that is, as a positive testimony to the difference that the gospel makes. This seems fair enough. It’s quite common for people to become interested in hearing more about the gospel because they are impressed and intrigued by the life that Christians live.

However, as an apologetic strategy or tactic, I worry deeply about ‘positive apologetics’. Of all the kinds of interaction we’re considering, it has the gravest risks attached.

For example—for something to be good or attractive, there must be a basis for evaluating it as such. Good or attractive according to whom, or according to which values? For positive apologetics to work, it has to meet the non-Christian world on its own ground, and seek to persuade it of the reasonableness or beauty of Christian belief based on what the non-Christian world already regards as reasonable or attractive. It has to adopt, to some significant extent, the worldview and assumptions of its audience, and shape the presentation of how Christianity is good or attractive in these terms.

It’s hard to see how this does not lead to a human-centred message that ultimately saps the gospel of its offensive power—a power which is encapsulated in the cross and resurrection. The cross is neither attractive nor reasonable; certainly not by the standards of the world. In fact, it is weak and foolish by those standards (as 1 Cor 1-2 makes very clear). Likewise the proclamation of Jesus rising from the dead to be the Lord and judge of all is hardly the kind of message designed to appeal to the intelligentsia (see Acts 17:32; 26:23-24).

If you lead with how attractive and good and reasonable Christianity is, how do you follow that with a gospel that defies these categories—that critiques and judges human standards of wisdom and goodness?

Positive apologetics also has a tendency to make Christianity the message rather than Christ. The pitch is for Christianity as an appealing or satisfying system of belief; or Christianity as an attractive lifestyle or community; or the church as a positive agent for good in our world. But the gospel is not Christianity. We do not proclaim ourselves but Jesus Christ as Lord.

You may be getting the impression that I’m a bit down on ‘positive apologetics’. I am. It worries me. In its defence, I can see how it sometimes functions as a useful form of ‘Pre-emptive objections’ (Type 3)—that is, if the accusation of the world is that Christianity is life-denying, negative and harmful, let’s remove that obstacle by showing how Christianity is life-affirming, positive and healthy.

All the same, I fear that positive apologetics leans too hard on natural theology, and tries to build a bridge from the world to God (which can never be done). It often ends up replacing the public preaching of the cross and resurrection with a public pitch for reasonableness and attractiveness. I worry that it seems to put God in the dock and offer reasons why the jury of the world should judge him to be attractive.

And that leads me to the final form of ‘apologetics’.

7. Prosecution (‘kategoria’)

If ‘apologia’ is the Greek word for making a defence in court, its counterpart is ‘kategoria’—to accuse, to prosecute.

The word is almost always used to describe a negative practice in the New Testament—such as Paul’s opponents accusing him of wrong-doing, or Satan accusing believers.

However the concept that ‘kategoria’ describes is central to evangelistic interaction, because we preach a message that puts the world in the dock (not the other way around). The gospel we’re commanded to preach is that Jesus “is the one appointed by God to be judge of the living and the dead” (Acts 10:42).

We see this in action in Acts 17. Paul critiques the folly of Athenian idolatrous religion (partly using quotes from their own poets to do so), and then calls upon them to repent, because Jesus has risen from the dead and will return as judge.

The message that we preach is good news—but it is so good because it honestly exposes and judges the folly and evil of our world and our hearts, and then proclaims God’s promise of forgiveness, reconciliation and new life in Christ.

In other words, the gospel that we preach by the Holy Spirit does what Jesus said the Holy Spirit would do after his departure—convict the world of sin and righteousness and judgement (Jn 16:7-11).

This ‘prosecution’ or critique can happen as we engage with people in conversation, and point out the inconsistencies and problems with the non-Christian position. It can happen as we unpick the illogical and dysfunctional patterns of non-Christian thinking or practice, or as we help someone understand that the mess their life is in has an underlying cause.

But it happens chiefly when we preach the gospel itself, when we proclaim Jesus as the crucified and risen Lord, and call upon people to stop rejecting him, and instead turn to him in faith and repentance. Evangelism has this prosecutorial aspect—which is why the diagram has ‘prosecution’ occurring at a couple of points on the spectrum.

To describe this kind of gospel interaction as ‘prosecution’ doesn’t at all mean that it is aggressive, hostile, angry or censorious. On the contrary, as Paul says of his own divisive ministry in 2 Cor 3-4, it is preached with a blameless straightforwardness and honesty that commends itself to everyone’s conscience. It is preached with fear and trembling and with tears (1 Cor 2:1-5; Acts 20:31).

Conclusion

It’s interesting that we tend to use the word ‘apologetics’ so frequently these days—even for forms of interaction that don’t really warrant the label. I wonder if this is because our stance towards the world has become essentially apologetic.

It would hardly be surprising if that were the case. Christianity has been on the defensive in our culture for 150 years. Could it be that we’re so used to being attacked and critiqued and marginalized that we have come to accept this as our fate and our role?

I fear we have. We’ve internalized the Enlightenment paradigm that man is the measure of all things. We constantly feel the need to justify the Christian position as reasonable and acceptable in the face of the prosecution of our culture—a now-dominant humanist culture that has been steadily criticizing and rejecting the gospel for the better part of two centuries.

And so we find ourselves crouched in a permanently defensive stance. We’re reluctant to speak out (because you can only have your head bitten off so many times). When we do speak, we lead with ‘apologetics’ of various kinds, assuming that our task is to make Christianity more reasonable and acceptable before a sceptical, accusatory culture. We ask our hearers whether perhaps they might give Christianity a second look, given that, you know, we’re really not as terrible as you think we are.

(I speak here to the impulses of my heart.)

Gospel proclamation by the Holy Spirit is not like this.

It prosecutes the world for its rejection of Jesus. It implores people to repent and be reconciled to the God they have alienated themselves from. It is not angry or aggressive. But it speaks the plain and honest truth, in weakness and fear and trembling.

We preach a gospel that critiques and confounds the world. But for those who have ears to hear, it is the sweet sound of salvation.

PS

This week’s post (and last week’s) started life as a discussion with the staff at CBS about these topics. One of the trainees piped up at one point and said, “Sounds like you’re saying that apologetics can be useful, but not as a replacement for evangelism”. Which pretty much captures it. The trend is for ‘apologetics’ to expand (in scope and importance), and to colonize the space where evangelism should be.

Do you see this happening? In your own heart and approach? In the Christian circles you move in?

Interested as always in your thoughts.

This week’s image keeps the classical painting vibe going — it’s Paul on Mars Hill.