Before we get to the subject of why Christian books are so vital, a follow up from last week’s post about being a ‘conservative’. Geoff Robson, who has taken over much of the editorial work I used to do at Matthias Media, got in touch to share a great quote from Peter Jensen. Geoff writes:

You reminded me of when PFJ became Archbishop (when I’d been working at Anglican Media for just over a year), and the media picked up on the label ‘radical conservative’ that had been applied to him at some point. He said he liked the label and accepted it (I had to transcribe the press conference for work, so I still have it filed away!). PFJ said:

Only a conservative could be radical. A conservative, to my mind, is someone who takes matters through to the foundations and is convinced about the foundations. In a postmodern world, this is rare. And indeed some of the flack we get, as a Church—with complaints about the way we behave and the way we speak—are simply a misunderstanding. We are very serious people, with a serious intellectual and moral agenda in a world where these things are treated somewhat as though they don’t matter as much.

Now, we have certain base convictions which are terrifically important to us. Having those base convictions frees us to be extraordinarily flexible about things that are of secondary nature.

Precisely.

But onto this week’s post, which is about bananas and Christian books.

The road to spiritual health is paved with Christian books

As a writer arguing in favour of Christian books, I feel a bit like a banana-grower arguing in favour of bananas—like my family did when I was growing up.

My dad’s people grew bananas at Dunoon, outside Lismore. My grandfather was even the president at one time of the North Coast Banana Growers Federation (he was the Big Banana, you could say).

So it is hardly surprising that our family consumed bananas in impressive quantities and in every conceivable format. We had them mashed on bread, sliced onWeet-Bix and baked in the Queen of All Cakes (banana cake with lemon icing). We ate them raw, frittered and barbecued. They were our morning tea, our afternoon tea and our sneaky late-night snack.

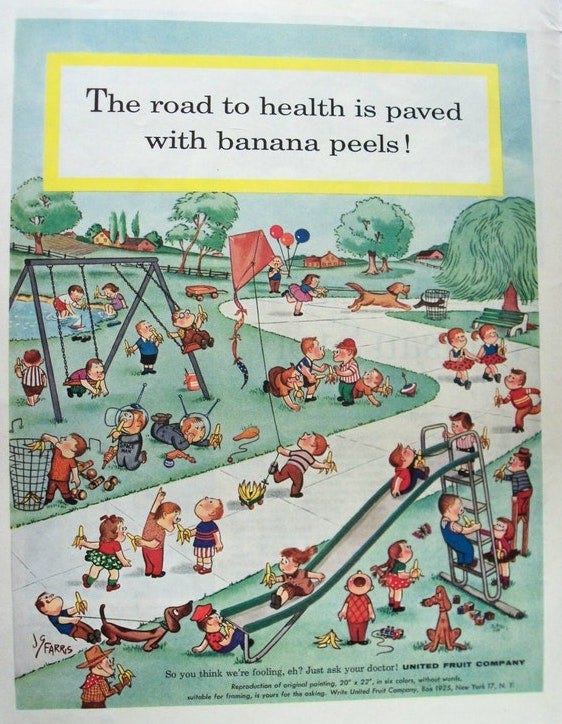

We were banana people, and had the banana key rings and other banana-themed merchandise to prove it. This poster was on the wall on the back verandah:

It always struck me that having a road paved with banana peels was also quite possibly dangerous to health. But perhaps the banana lobby could be forgiven for overlooking this. What else would you expect them to be but blindly and joyously pro-banana?

I feel rather like this in arguing that the road to spiritual health is paved with Christian books. What else would I say, as a life-long Christian writer and publisher?

However, it’s a little different. I’m not sure that a conviction about the all-purpose benefits of bananas was the reason my grandfather spent his life growing and promoting them. Perhaps it was—maybe the banana passion came first, and then the desire to grow them. But it has certainly been that way with me. It’s precisely because of a strong conviction about the value of Christian books that I’ve spent my ministry life writing, editing and publishing them.

That conviction has three pillars.

The first is a theological belief in the power of the word. It’s a cliché to say that we live in a visual age where people prefer to watch rather than to read. This is true, but only in so far as it is a description of every age. People have always preferred the immediacy of the visual. This is why that little thing called idolatry—the worship of a visual representation of the divine—is condemned so widely and vigorously in the Bible. It has always been humanity’s besetting sin.

The ‘humiliation of the word’ (as Jacques Ellul described it) is a feature not just of modernity but of history. Our rejection of God is a rebellion against him who cannot be seen, and a turning to the worship of created things that can be seen. Rather than seeing in the creation evidence for the invisible God, and honouring and thanking and listening to him, we turn away and suppress that truth. We turn to what can be immediately seen and worship it instead.

The visual is immediate and uninterpreted. It has no words. It is ‘dumb’, as Isaiah describes the idol that we make out of a piece of wood. Five minutes ago we were barbecuing bananas over it; now we’ve fashioned it into a shape and are thinking that it provides the meaning for our lives. The visual suits us very well, because we simply experience it and decide for ourselves what it means.

A preference for seeing and watching over listening and reading is more than a difference in learning styles or personal taste (although of course it is partly that). It is also deeply rooted in our human unwillingness to learn the truth about ourselves and God by humbling listening to his word. The Christian, by contrast, lives by faith not by sight, and our faith is in the word of Christ that we hear (2 Cor 5:7; Rom 10:17).

However, if it is God’s powerful word that we should turn to and believe, why are Christian books important? Why is the Bible not the only book to be published and read?

This brings us to the second foundation for the importance of Christian books and reading, and it is also theological. The word of God is authoritatively revealed and inscripturated in the Bible, and the Bible remains the supreme and only source-book for our knowledge of him. But his word is communicated and does its powerful work as his people speak it. Whether in the teaching-preaching speech of pastor-teachers, or in the one-another speech of his people in multiple ways, God’s word is spoken and heard and grasped and understood through the mediation of human speech.

Christian books are vital because Christian speech is vital. We receive God’s word in Scripture, and then by his Spirit we preach it so that it can be heard and believed. We preach it and teach it, and explain and expound and admonish and encourage and exhort it. And we write and read it.

But this raises the third pillar of Christian reading. Why reading? Why not just hearing? Why bother with books if we have sermons and podcasts?

The answer is obvious to anyone who has enjoyed the benefits of not just listening to biblical sermons but of reading the Bible for yourself. Something different happens when we read the Bible ourselves, because reading is a different mode of receiving and hearing and engaging with words. Reading is more flexible, and offers different opportunities for learning. When we read, we can speed up or slow down. We can skim and gain an impression of the whole, and then go back and pore over words and sentences, and milk them for meaning. We can pause and ask mental questions, and then re-read for possible answers. When we read a particularly striking sentence or phrase or metaphor, we can stop to appreciate it and allow its power to penetrate our minds. This is why the Bible itself recommends reading and re-reading and meditating over the word so that its sweetness enters our soul (as in Joshua 1:8 and most of Psalm 119).

Reading, in other words, is deep and interactive. We are not simply receiving the words at the pace and direction of the speaker; we can engage with the words, and draw more from them.

This is why a book or an extended essay can mount a significant argument, or take us deep into the truth of some aspect of God’s word, in a way that a sermon or talk or conversation cannot. Reading helps us to think and to change our minds—again, in a different way from what hearing or listening can achieve.

If Christian growth includes the renewal of the mind, then the road to spiritual health is indeed paved with biblically faithful Christian books. In God’s providence, he has given us this powerful means of learning and growing in our knowledge of him. Why would we not take advantage of this blessing that God has provided? When our hearts and minds are so prone to spiritual ill-health, why would we turn up our nose at the rich nutrition that a diet of Christian reading supplies?

I guess because we’re human. We’re lazy and inattentive, even to our own detriment. We prefer things on our own terms.

Sometimes, in the end, we’d rather just eat bananas.

PS

So much else comes to mind on this topic, especially as a I look back over the past several decades. We promote books and reading in church far less than we did. We might say that this is because ‘people don’t read any more’, but this is a consequence of our inaction more than a cause. It was no different in the 1980s and 90s. Everyone then said that reading was dead because of television, just as everyone today blames the internet. But in the past, churches that promoted and sold and discussed books regularly unsurprisingly fostered a healthy culture of Christian reading. We could easily do so again.