Dear friends

A couple weeks ago, we chatted briefly (in response to an email from Lindsay) about the differing nature of the ‘tribes’ we hang with, and how the fellow travellers we find ourselves in partnership with in one context might not be people we choose to work so closely with in others.

As part of our discussion, Phillip said this:

If we go to another part of the world to preach the gospel—and I’m very glad Lindsay has—the fact that there are fewer people with whom we share common ideas than we did at home in Sydney … well that’s part of being a missionary. We might find ourselves having less in common with our friends than we did at home, but we still have certain fundamentals in common. And so our ‘tribal relationships’ may be a little looser.

And that got me thinking: How might we articulate those fundamentals we have in common? What are the really core things we stand for, and which determine (in various contexts) whom we stand with and work with?

I brought my draft thoughts on this question to a pretty lengthy conversation with Phillip (that you can listen to above). Here’s the much shorter, summarizing piece I wrote as a result of that conversation.

TP

What we stand for

(and whom we work with)

The Federalist Society is arguably the most influential legal association in the United States. It was the group that put together the list of names from which President Trump chose judges for the Supreme Court. In US legal circles, FedSoc is the gorilla in the room.

Whenever the Federalist Society meets, they always recite the three core principles for which they stand, as follows:

The state exists to preserve freedom.

Separation of powers is essential to our constitution.

It is emphatically the role of judges to say what the law is, and not what the law should be.

Now you might not completely understand all that, or agree with all of that, but if you know anything about the US constitution and the traditions of US jurisprudence, you would know exactly where the Federalist Society stood, and what their mission was.

Could we evangelicals do something similar?

Could we recite three statements that made it clear what it really meant to be an evangelical Christian, and which therefore also provided some criteria for unity, cooperation and fellow-working? Could we have a little gospel truth test for knowing whom to stand with and to work with?

This is a more complicated task than it first appears, and we won’t be able to cover all its complexities in this short piece. For example, while we would want to say that to be evangelical is to believe in and fight for certain gospel truths, the nature of that same gospel is to welcome and include people, not censoriously exclude them. Evangelicals have a bias towards welcoming sinners in so that they can hear the gospel and be saved. And yet the New Testament is also clear that the wonderful, loving, gracious message of the gospel does divide and exclude people, and that there are lines that cannot be crossed.

Perhaps this is where we could start—with those places in the New Testament where some red lines are drawn, and where people or ideas are excluded.

Let’s summarize the main ones:

In 1 Jn 4:1-3, you can tell who is really from God by whether they confess that “Jesus Christ has come in the flesh”. In context, this means something like: “someone who believes and testifies that the incarnate Jesus rose bodily from the dead to be God’s ruler and Christ”. Your belief about who Jesus is, as the risen ruling Man, the Christ who fulfils God’s purposes for humanity and the world, is a simple test for whether a spirit is from God or not.

Also in 1 Jn 4, the apostle also says: “We are from God. Whoever knows God listens to us; whoever is not from God does not listen to us. By this we know the Spirit of truth and the spirit of error” (v. 6). Another red line test is whether you are willing to heed and obey the apostolic word or not—that is, whether you are willing to submit to Scripture or not.

These first two points are connected of course. It is the apostles who preach the true gospel about the crucified and risen Jesus Christ. Rejecting one involves rejecting the other. A similar connection is seen in 2 Cor 11 where Paul is worried that the Corinthians will accept “another Jesus” and a “different gospel”, the one that is being preached by a rogue group of “super-apostles”.

Galatians also famously draws a red line about the impossibility of accepting a “different gospel” other than the one originally preached by Paul (Gal 1:6-10). The issue this time is justification by faith (as opposed to justification through works of the law).

Interestingly, though, fidelity to the original apostolic Christ-centred gospel is not the only test. How you live or behave can also be a test, since what you do expresses what you really believe. It’s not those who say ‘Lord, Lord’ who will be welcome in the kingdom, but those who do the will of Jesus’ Father (Matt 7:21). Similarly, in places like 2 Tim 3, the false teachers who are to be avoided have the appearance of godliness but deny its power, as seen by their wicked character and behaviour (2 Tim 3:1-9).

If we wanted to draw these together, we might say that—surprise, surprise—it’s the gospel that supplies the definitive tests. The gospel is the announcement (which we find only in Scripture) of God’s gracious work in Christ—to send his Son as a man to die for our sins and rise for our justification, to set his risen Son on the throne as the ruler and saviour of his people, to redeem a people for himself (a people who in response to his gospel are zealous for good works).

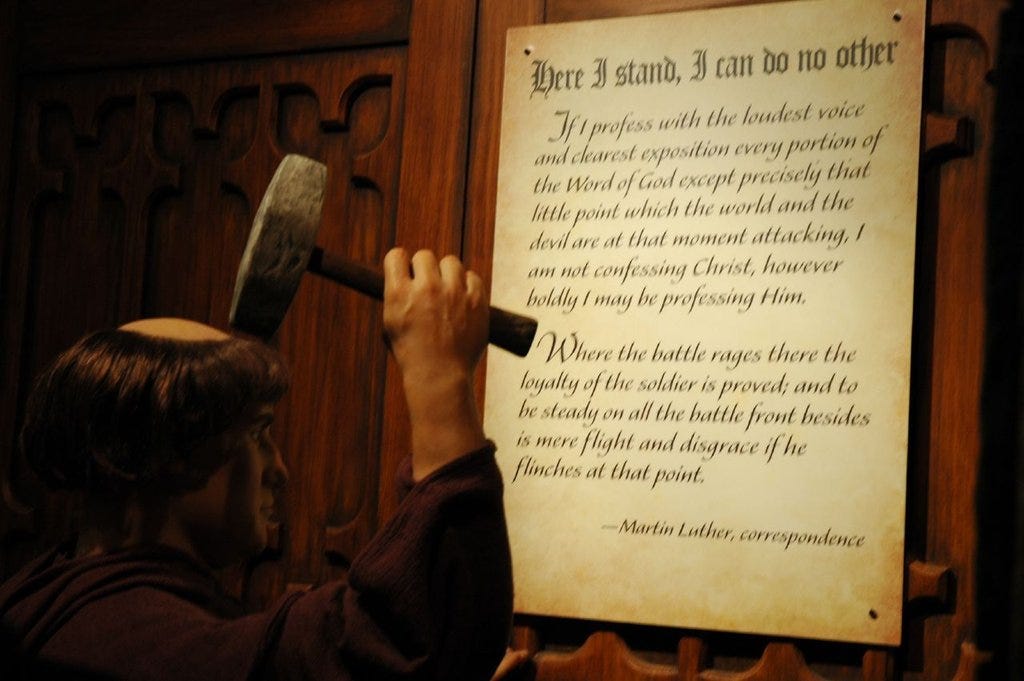

To be an evangelical (or ‘gospel person’) is to keep taking our stand on these truths—on the biblical, apostolic word which teaches a crucified and risen Christ as the only justifying saviour, as the only Lord whom we trust and obey, as the final source of truth about God and ourselves.

It’s very interesting to me how often the words ‘from God’ appear in all of this, and in 1 Jn 4 in particular. The red lines of the gospel keep putting God and his gracious action at the centre; they keep insisting that it all comes from him. He is the one who sends his Son from heaven to die for our sins and be crowned as the Christ; he is the one who is rich in mercy, and raises us up to new life in Christ by his grace alone . “All this is from God”, as Paul says in 2 Cor 5:18, “who through Christ reconciled us to himself”.

By contrast, false gospels and false teachings almost always involve a dilution of the ‘from God-ness’ of the gospel. They want to find a place for human effort, human merit, human reason, human traditions, human experience. In standing for the gospel, we stand for the sovereignty of God in revelation and redemption—it all comes from him, not from us, not from the world. (1 Cor 1-4 is really an extended application of this idea.)

This is where the famous ‘theological quadrilateral’ comes in as a helpful visual summary of what evangelicals stand for, where we can agree to differ, and where lines have to be drawn.

Originally, this diagram was conceived as a way of talking about authority. The Bible teaches us about God and everything, but as we read it we cannot avoid using our God-given reason, being affected by our experience, and learning from our traditions and institutions. We read Scripture using our minds/reason, in the context of our experience of the world and as part of a community or tradition of reading where we listen to others.

However the Bible sector is the first and final authority. It should inform and drive our reason, experience and tradition, and it should be our flag and fortress when human reason, experience and tradition conflict with what the Bible says. At various points you have to draw a line between the sectors of the quadrilateral, and decide where you stand.

The Bible sector is really the ‘from God’ sector. It’s a way of saying that our gospel understanding and practice must ultimately come from him, not from us or from the world. Our access to God and all that we know of him and experience of him and learn together of him comes to us through the Word, not from any human source or power. And so we submit to him and his gospel Word, in faith and repentance, even when—and especially when—our reason or experience or tradition calls us in a different direction.

The other three sectors really represent the three classic alternatives to evangelicalism in Christian history—liberalism (where reason ultimately trumps the Bible), pentecostalism (where experience finally matters most), and Roman Catholicism and all forms of churchy institutionalism (where human traditions, teachings and churchly activities usurp God’s supremacy in revelation and salvation).

Some practical implications

There is so much more that could be said, but let’s stop at this point to note three implications of what we have articulated.

a. Evangelicals are people who by God’s grace take their stand in the ‘from God’ sector of the quadrilateral. They call on others and seek to persuade others to join them there, and they also keep exhorting and persuading and sharpening each other to grow in understanding and to stand firm. This means that (as in the case that Lindsay originally raised) you may find yourself working in gospel fellowship with people who don’t stand quite as firmly in the evangelical sector as you do—who flirt with the edges of liberalism (e.g. in holding an egalitarian view of men and women and ministry), or who place too much emphasis on experience (e.g. in accepting a pentecostal view of church and worship), and so on.

We may still work together, even as we continue to search the Scriptures together (which we are both committed to obeying) in order to come to a better understanding.

But work together in what? This leads to a second implication.

b. We can work with others only in as much as we agree with them.For example, we couldn’t be united in gospel work with a Muslim imam, but we could work in unity with him to argue for the value of religious education in schools, because on that issue we agree and are united. Likewise, we could work in various forms of gospel partnership with egalitarian brothers and sisters—even while disagreeing quite strongly about egalitarianism. However, it would be difficult to cooperate together in planting a church because the fundamental issues of whether or not we should have women preachers or elders would divide us.

This leads to a third point.

c. Actions instantiate ideas and create division. As long as we are debating and discussing our differences, we can (to some great extent) continue to work together. But once our ideas are put into action, division often results (and sometimes rightly so). It’s when Peter pulls back from eating with the Gentiles that the gospel issue comes to a head in Galatians.

To take a contemporary example, evangelicals have different views about baptism, and can debate these in fellowship. However, once we put our ideas into effect—say, to make church membership available only to those who have been baptized as an adult by full immersion—a limit is placed on our cooperation. I have dear Baptist friends and brothers with whom I have a deep unity in the gospel and with whom I work on all kinds of gospel projects—but it would be very difficult for us to plant a church together, or even be members of the same church, because a church must have a baptism policy. The practical instantiation of the disagreement will limit the spheres in which we can work together.

Another more sobering example would be the debate about whether practising homosexuals can be ordained as ministers in the Anglican Church. While this is in the realm of ideas, we can still at least sit at the table together and debate. However, once the deed is actually done—that is, when openly practising homosexual people are actually ordained to the ministry—then gospel fellowship becomes impossible.

Even in this latter case, some forms of cooperation may still be possible. We might still gather in synods to decide the practical arrangements of the property we share ownership of, and so on. In other words, in the sense that many denominational organisations are now little more than religious real estate companies (and sadly, this is what many of them have become) then we may continue to cooperate in managing the real estate. We just can’t fellowship as Christian brothers and sisters. We may go to the synod and conduct its business, but we couldn’t share in the Lord’s Supper together. This is not at all a situation to be desired, but it may be necessary, given our historical ties and arrangements.

~~~~

Now, these three practical implications don’t rise to the level of the Federalist Society’s three statements of core belief. And in the articulation of the theological principles (above) I haven’t really boiled them down to three statements we could all recite. And perhaps that’s s good thing.

However, I hope that some clarity has emerged. What we stand for (and against) is determined by the biblical gospel itself. And whom we therefore stand with and work with is likewise determined by the nature of the gospel work and fellowship that is involved.

Evangelicals will always have a gospel bias to love and welcome and include, as God has graciously loved us. But because of the truth and glory of that same gospel on which we stand, we will also have a grieving but resolute acceptance of the division that results when people choose to stand somewhere else.

PS

Some extra resources to chase up on this topic:

A short classic case study about the issues we’ve been discussing is Student Witness and Christian Truth, by Robert M. Horn. It’s an excellent discussion of how these questions of truth and fellowship were worked out in student ministry in the early 20th century, the result of which was the formation of what became the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students.

For a longer discussion of this whole question, you can also chase up The Limits of Fellowship, an essay (with related audio) that Phillip wrote back in 2008 about the question of whether the Anglican bishops of Sydney should go to the Lambeth Conference.

Here’s a bit more on the Federalist Society for you US political junkies.

It was three judges chosen by the Federalist Society, and appointed by Donald Trump to the US Supreme Court, who were decisive in recently overturning the Roe v. Wade abortion decision (Justices Gorsuch, Kavanaugh and Coney Barrett)

However, most of the mainstream media reports that I read were vague or misleading about the reasons they overturned it, which really have to do with the core beliefs of the Federalist Society. These judges struck down the constitutional right to abortion in Roe v Wade not because they were against abortion as such (as ‘right wing’ or ‘conservative’ judges), but because they argued that the US constitution contained no such federal right, and that therefore the issue should be decided by the various states. In other words, it was because they saw their role as saying what the law of the Constitution actually is, not what people think it should be, that they reversed the previous decision.

This goes back to our discussion of ‘conservatism’ some months ago. Much depends on what you’re seeking to conserve. The Federalist Society and its judges are not seeking to conserve a particular moral or political set of values so much as a stance towards the Constitution and the American founding.

Interestingly, on this very basis these same judges have ruled against Donald Trump at several key points, as have other Trump-appointed Federalist Society judges in lower courts, much to his displeasure.