I did some training with the CBS staff recently on ‘apologetics’, and how it relates to ‘evangelism’. And as I did so, I realised that one of our problems is simply that the word ‘apologetics’ gets used today to refer to such a range of different things.

And so to clear the ground a little and clarify understanding, I put forward the following ‘seven kinds of apologetics’. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say, ‘Seven kinds of Christian speech or interaction that are sometimes called apologetics’.

See what you think.

Seven types of ‘apologetics’

What is apologetics?

Let’s start by saying that apologetics is not evangelism. Evangelism is the proclamation and explanation of the historical truth of the gospel—that God sent Jesus Christ to die for our sins, that he raised him from the dead to be the Lord and Judge of God’s eternal kingdom, and that he now calls on all people everywhere to submit to Christ in repentant faith (see Boxes 4-6 of Two ways to live!).

But gospel proclamation, pure and simple, is not the only kind of interaction we have with people. There is also conversation and reasoning and debate—both pre- and post-evangelism—and we have come to label much of this ‘extra-evangelistic’ interaction as ‘apologetics’.

I’m not sure how far the word ‘apologetics’ can actually stretch. In fact, strictly speaking, I think only two of the seven kinds of interaction I’m about to outline are really ‘apologetics’ per se. That doesn’t mean that the other five aren’t valid or useful. They mostly are. But some clarity will help—especially since a common tendency is for apologetics to expand and colonise the space where ‘evangelism’ should be. (But more on that below).

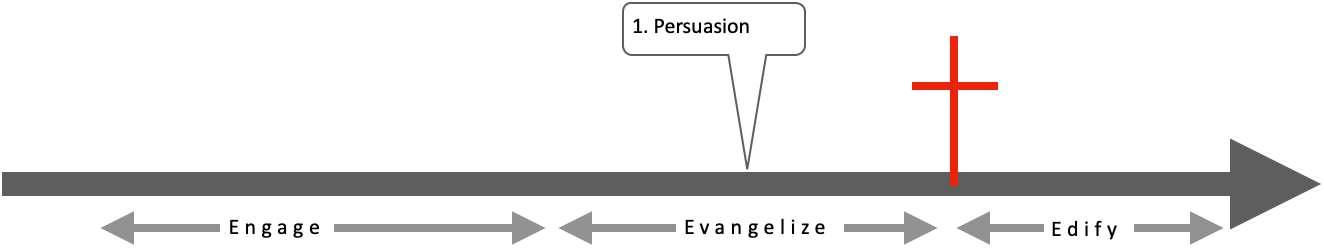

To conceptualize these seven kinds of ‘apologetics’, I’m going to use the ‘moving to the right’ concept that we looked at a few editions ago—or at least the left half of that diagram which focuses on engaging and evangelizing non-Christian people to move them to the right, towards coming to know and trust and serve Christ.

Like this:

The different kinds of ‘apologetic’ interactions we’re looking at occupy different points along this spectrum. Types 1-3 are in the ‘evangelize’ zone, and types 5-7 are more down the ‘engage’ end of things, and type 4 is over in the ‘Christian’ zone. It’s never as neat as that in actual conversation, or in the sermons we preach. But categorizing them in this way can help us understand what we’re doing when and why.

1. Persuasion

When we’re right in the middle of evangelism—of actually explaining the meaning of the death and resurrection of Christ—we will provide various arguments and reasons to support our proclamation. Like Paul, in 1 Cor 15, we may argue that the meaning of Christ’s death and resurrection is grounded in God’s age-long plans as revealed in the Scriptures, or we may support the truth of the resurrection by pointing to the witnesses who saw him. (Interestingly, Peter’s sermon at Pentecost covers much the same ground.) Or we may spend time persuading people of the nature and reality of their sin, and their plight before God, as a means of explaining why the death and resurrection of Christ is such wonderful news.

Reason, argument, persuasion—these are natural aspects of explaining and commending the gospel. We see the apostles and evangelists doing this often and in different ways in Acts (e.g. Paul’s ‘reasoning’ and ‘persuading’ in Acts 18:4 and 19:8).

Is this ‘apologetics’? Well perhaps not as such, although sometimes it comes close. That’s because ‘apologetics’, strictly speaking, is a defence of something or someone. An ‘apologia’ is your answer to someone’s objection or accusation (this is what the word means).

If you’re explaining to someone why your message is true and trustworthy, are you ‘defending’ it? Well, sort of. It’s interesting that Paul’s ‘defence’ (apologia) of himself and his ministry in Acts 26 ends up being a gospel sermon.

In any case, even if we think it might be a stretch to give it the label ‘apologetics’, let us agree that persuasive, well-argued gospel proclamation is a good thing!

2. Answering objections

Classically speaking, this is where ‘apologetics’ really lives. You preach or put forward your explanation of the gospel, an objection or accusation comes back, and you respond. You make a defence.

We see it in 1 Peter 3:15 where Christians are called to “to make a defence to anyone who asks you for a reason for the hope that is in you”. We see it in some of Paul’s speeches in Acts where he makes his defence against the accusations that have been levelled against him, and (by implication) against the gospel that he preaches (e.g. Acts 22:1f; 24:10f).

Apologetics, in this sense, comes after evangelism. (This is why I’ve positioned it towards the right-hand side of the evangelism zone on the diagram.) It answers the questions, objections or accusations that are raised against the truth of the gospel—things like these:

How do you know that the historical events you’re proclaiming actually happened? (This is where ‘evidential apologetics’ comes in, defending the historical reliability of Scripture, the truthfulness of the Gospel accounts, and so on.)

Isn’t this message that you’re preaching socially or politically destructive?

If Jesus is Lord of all, what about those who’ve never heard of him? How will they be judged?

If God is supposedly so powerful and loving in sending and raising Jesus, why is there so much suffering in the world?

If sinners are going to be judged, does that mean that all gay and trans people are headed for hell?

And so on.

(Kel Richards’s under-appreciated little book Defending the Gospel is one of the best examples of classic ‘defensive apologetics’ of this kind that I know of. It works its way through the main points of the gospel, and shows how to answer the common questions and objections that arise at each point.)

3. Pre-emptive objections

Sometimes, in practice, we try to deal with some of these common objections before we get to proclaiming the gospel itself. We assume that our hearers already have objections—because they have already heard some version of Christian teaching and already have reasons for rejecting it.

Strong versions of these existing objections are sometimes called defeater beliefs— existing beliefs or objections that rule out the truth of the gospel before we’ve even started to explain it. “I don’t have to listen to you and your gospel; I’ve already dismissed them because of X.” And X could be objections like these:

Science has disproved God. I don’t need to listen any further.

My life is quite fine without God and Christianity; I have absolutely no need of them, even if they were true.

No normal, rational, modern person can believe in the Christian gospel. We’ve outgrown it.

Jesus might be interesting, but ‘Christianity’ and ‘the church’ are so poisonous and horrible that I have no interest in listening to you.

The first half of Tim Keller’s The Reason for God is a good example of this kind of apologetics. He begins by dealing with some common objections or ‘defeaters’ before turning to the gospel itself in the second half of the book. An even better example (because it does a better job of the ‘gospel’ bit in the second half), is Naked God, by Martin Ayers.

‘Pre-emptive apologetics’ of this kind is valuable, but it is also not without risk:

The person you’re speaking to may not in fact have the objection you’re answering—and all you have done is waste their time, and possibly put an objection in their mind that they hadn’t previously considered.

It puts you on the back foot from the outset. Rather than leading with the positive message that you love and are excited about (the gospel of Jesus), you lead with the negative reasons why this message isn’t believed by people.

It can reframe how you preach the gospel itself. If you pre-emptively deal with the objection, for example, of whether Christianity has been a bad thing for humanity or not, it’s easy for Christianity and the church to become the focus of your message (rather than Christ himself). You can end up seeking to justify the truth of the gospel on the basis of whether it is a net good for human life and society or not.

However, the major risk with too much focus on pre-emptive apologetics is the one in our own heads—we start to believe that if we can first just clear away these objections, then voila! Our hearers will accept the truth of the gospel and believe.

We need to trust what the Bible tells us about the people we’re seeking to evangelize—that the underlying basis for unbelief is moral and spiritual corruption. Deep down, all people know very well that God is their good and powerful Creator. But we all suppress this truth and exchange it for a lie, with the result that our thinking and values become hopelessly compromised and distorted (Rom 1:18f.). When faced with the light, we prefer the darkness, because our deeds are evil (Jn 3:19).

It’s in this sense that we should treat people’s objections respectfully and courteously but not seriously. The problem goes much deeper. (See my earlier post on ‘not taking unbelief seriously’ for more on this.)

We must still persuade and give good reasons for why our proclamation is true (because if Christ is not raised then our faith is futile). And we can’t continue in conversation and persuasion without addressing the questions that people raise along the way.

But we mustn’t think that answering objections (pre-emptively or otherwise) is the key that will unlock the door of someone’s heart. Or that apologetics is the necessary bridge across which the gospel must walk.

The gospel is the power of God for salvation, not apologetics.

4. Building confidence

This brings me to the final variety of ‘apologetics’ that I will cover in this post.

A key function of classic defensive ‘apologetics’—the kind that answers questions and objections—is to build the confidence of Christians in their faith and proclamation.

When the world throws stones at the gospel, Christians can be the ones who end up bruised. Doubts creep in. Confidence wanes. If all these smart people reject the gospel, and they have all these snappy one-liners and objections, then maybe I’m just naive to keep believing.

Answering these objections, and showing how shallow and insubstantial they usually are, brings real comfort and confidence to Christians. It bolsters their defences, and strengthens them not only to grasp even tighter to the gospel, but to be bold in sharing it.

By defending the gospel, we defend those who have put their trust in it.

PS

Well, there’s a quick summary of types 1-4. I’ll get to numbers 5-7 in next week’s post. But feel very free to send in any thoughts or reactions in the meantime.

As always, feel very free to copy and use this article (and next week’s) to talk about apologetics in your small group or staff team.

Thanks for the continuing stream of emails and messages coming back. It’s great to keep hearing from you. One recent encouraging message (from Bek) came in response to ‘How to grow left-lookers’ (https://www.thepaynefultruth.online/p/how-to-grow-left-lookers). Here’s part of Bek’s email:

Two lines from your article caught my attention.

The first—“people who are stuck in complacent, self-focused Christianity”—reminded me of the CBS catch phrase 'don't settle for middle-class Australian life'. This is so easy to do and I try to challenge myself on this often. But the thought that this isn't just about making sure that we don't allow our jobs or comforts to become idols, but that we also need to be actively pursuing the growth of God's kingdom—I think comes as more of a rebuke.

Which ties in with the second line that struck me—“it is maturity in the lived practice of that knowledge”. As university-trained professionals who have come through CBS it can sometimes feel like having the head knowledge is good enough, but if we aren't living it out visibly in our day then are we truly mature? Or do we actually need some of that milk reminding us of the amazing gift of God's grace, to see the gravity of our sin and the beauty of the cross so that we honestly desire others to know Christ and glorify God?

Had to scratch around a bit for an image this week—this painting is allegedly Paul making his defence before Agrippa.